Decisions can be exhausting. You don’t have to be in a life-altering scenario for them to be taxing: Anyone who has ever read a compelling dinner menu knows that the smallest choice can take a lot of thought. Every calculation, no matter how quotidian, requires cognitive (and emotional) space. And it adds up.

That’s the beauty of habit; it’s your brain’s way of unburdening you of the need to make decisions. It’s an automatic process that’s brilliant for those repeated behaviors that are good for you, and not-so-brilliant for the repeated behaviors that are not. But despite their divergent long-term effects on our lives, good habits and bad habits have the exact same origins.

That paradox is the subject of research psychologist Wendy Wood’s illuminating book, Good Habits, Bad Habits: The Science of Making Positive Changes That Stick. In unpacking the reality of what habits really are and what makes them tick, she helps you imagine simple ways you can most effectively design the ones you want into your life.

We asked Wendy to give us a primer on why we form the habits we don’t want—and how we can form new ones that we do want. She tells us why willpower alone isn’t enough, why instant reward is essential, and the special challenges (and upsides) presented by a pandemic.

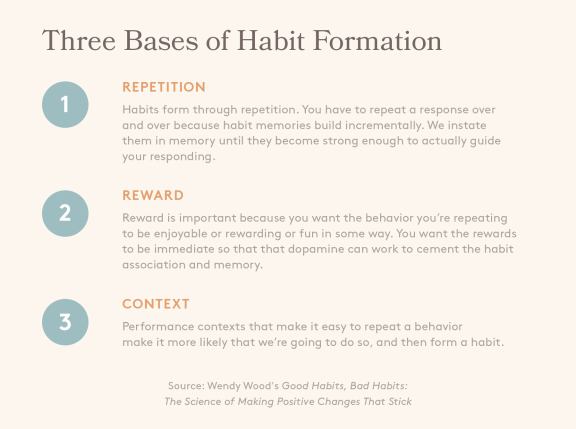

Our habits aren't part of our conscious awareness. Instead, they are a memory system that develops through our experiences. As you do things, you are storing information in habit memory, and you're storing a very specific kind of information. You're connecting what you do in a given context to get some reward. The reward could be that you get to work on time, or it could be that you get a cup of coffee in the morning after you make it.

All of those things are outcomes that we're seeking when we first start doing something. Then as we repeat behavior and habit memory builds, we start responding more automatically to the context around us. We act on those habit associations in memory—between context and the response we've given in the past—to get a reward. And we do so without having to make decisions. That is the basis of habit memory: They're sort of summaries or shortcuts of past experiences. What's worked for us?

The habits we form are working for us at least in the short-term. That's the reward. You can imagine back when we were all in the office if you have a tight schedule one day, you might get some junk food from the vending machine for lunch, and you do that a few times, and that fills you up and meets your immediate need and starts being a habit, so around lunchtime, you start thinking, "Vending machine. Okay, I'll walk down there." That's something that worked immediately and would form into a habit very quickly. But in the long-term, it's not really something that's good for your health. It's probably not a diet that you would prescribe or adopt if you had a choice.

We form habits from convenience and to make our lives easier; we repeat behaviors that might not actually be the best ones for us. That becomes clear in the long run when you're not feeling so good and you start gaining weight; when you start having problems from the choices you've made in the past. We're forming habits all the time, but they're not necessarily always the ones that we would want to form.

All of this has to do with the neural architecture that we have as humans. We think of our brains as just sort of one unit—as one thing that helps us that's part of how we think, that's part of how we feel, that is full of our memories. But our brains actually evolved in fits and starts throughout the whole history of the human species. They developed capacities and lost them. As a result, we have a bunch of interconnected but somewhat separate networks. And the network that is part of your habit memory system is relatively separate from the networks you use to think and make decisions.

That's why sometimes our habits correspond with what we want to do right now and sometimes they don't. There's a funny disconnect between our habit memories and our conscious decisions. And that's nowhere as evident as when we are acting on a bad habit. Bad habits are just the same as good habits. They're just not consistent with our current goals. They might've been consistent with our past goals, as in my vending machine example, but they're not consistent with what we want right now.

Those are the habits that we're most aware of. Because the ones that are consistent with our goals, if we don't have conscious awareness that we're acting on habits, we just assume, "Well, I must've wanted to do that and that's why I did it." But with bad habits, our behavior is running off in ways that we consciously might not want, so we're very aware of that.

Many habits form when we do set new goals for ourselves. If you decide that you're going to start an exercise program and you do it consistently for several months—and you find some way to repeat the same behavior over and over—with enough time, that will become your habit.

Goals are helpful sometimes for starting a new habit. They can set up on the right path, but the habit memory does not depend on your goal. It depends on the fact that you've repeated a behavior over and over in a given context so that you formed those context response associations that are habits in your memory system.

The way most people think about behavior change is, "I'm going to make a decision. I'm going to do it, and I'll exert willpower, self-control. Might involve some self-denial, but I'm going to make it happen." They put a lot of effort into that and that works in the short run. It's great if your goal is to do something like, "Oh, I'm going to join the retirement program at work." All you need then really is willpower: With willpower and a little planning, you can make it happen. But when it comes to behaviors that you have to repeat over and over—like most important things in life, health, beneficial, happy relationships, being productive at work, saving money—all of those things require repeated behavior.

Willpower is not strong enough to get us to repeat behaviors regularly, which is why we can change our behavior in the short run. Most of us can make ourselves go to the gym once or twice. We can stick with a diet for a few weeks, but after that, it starts to seem difficult. It's not much fun. We tend to fall back into what we were doing before, and that's the problem with willpower. It just doesn't last long enough for us to really use it for those kinds of repeated behaviors that we all have to figure out how to do in order to live healthy, happy lives.

It's been an experience of real context change, right? The context that used to activate our old habits has switched. People started working from home, so we don't have all of those cues about getting to work on time, getting dressed, having to work in the office until 6:00 at night. None of those things are there anymore. Some people lost their jobs. Some people are helping homeschool their kids. We're all living very different lives than we did 12 months ago.

That huge context change disrupted all of our habits. And that's part of the reason why people reported feeling overwhelmed and really challenged at the beginning of the pandemic, because we had to start making decisions about things that we were doing habitually, automatically. We had to decide, "Okay, what time am I getting up today? Do I have to get dressed? How much of me has to get dressed, just the top half? Can I wear sweatpants with a nice work outfit? How do I do this?"

All of that has required thinking through new behaviors—and that takes energy and it takes thought. We couldn't rely on our old habits anymore. We had to create new ones and we had to do it quickly and all of a sudden.

But it's also difficult now because we're having to try to think through how we are going to meet our goals now, but in a way that might be sustainable after the pandemic is over. Personally, I used to go to a gym. I used to take yoga classes, and of course, you can't do that anymore. I joined a yoga studio that was meeting outside and that was great over the summer, and that was a good thing to do that organized my workout schedule. But then it got cold. And now I have to decide how I'm going to continue to exercise, and do I really want to invest in some expensive exercise equipment? Am I going to use it after the pandemic? All of this requires so much thought.

Absolutely. This is also an opportunity for some people. People are cooking more at home, and we eat better when we cook meals at home. That's a great thing. Unfortunately, people are also moving a little less because we are trying to social distance. But there's also data suggesting that people are spending more time outside.

So there are some indications that there are behaviors that have changed that actually work to our advantage now. The question then becomes, How do you keep them after the pandemic is over? How do you make sure that they persist in some way?

We know that people do better if they set ambitious goals for themselves. But those sorts of life-changing, "I'm going to change everything in my life" resolutions are not a very effective way of going about change. I would suggest people focus on one thing at a time. Focus not so much on your own willpower and self-control and determination, but instead focus on setting up the environment around you to make it easy for yourself.

Let me give you an example. My oldest son is a bike racer and he is a committed athlete. He works out constantly. He races on the weekend, but he also has a job. And he has found that if he goes to work and comes back home, he has great plans to use his bike trainer in the evening, but he's tired. If he doesn't put his trainer in front of the sofa at night, then when he comes home, he's likely to just flop on the sofa. But with the trainer there, he has to actually move it out of the way in order to sit on the sofa, so he's much more likely to actually get his workout in if he sets his trainer up before he goes to work. That's an example of someone organizing their environment to make the behavior easier.

If it was possible to just rely on motivation all the time, he wouldn't need to do that because he's so highly motivated. But motivation isn't enough. Because being motivated in the morning doesn't take into account how tired you are when you come home from work, and that you might be frustrated or focused on something that happened at work that makes working out less attractive than when you left home in the morning. Organizing your environment allows you to keep your goals and keep your plans with the least amount of effort—and that's what we all need, is an easier way to meet our goals.

It's helpful for people to think about their environment, everything around them, in terms of friction.

For example, when people make New Year's resolutions, they think that if they convince themselves and exert willpower, that's going to be enough. A study was done with elevator use a number of years ago where the researchers did just that: They put up signs to convince people that it would be better if they took the stairs instead of using the elevator. The researchers put up signs that said, "Take the stairs. It uses calories. Take the stairs, save the environment." But those signs had no effect on people's use of the elevator.

What the researchers did is they slowed the closing of the elevator door by 16 seconds. And that was enough to reduce elevator trips by a third. Time is friction.

A month later when the researchers put the elevator doors back to their original speed, people kept taking the stairs because they had formed habits to do so. That's an example of how you can use friction in your own life, making it more difficult to do the things you don't want to do, and thereby encouraging yourself to engage in behaviors that are consistent with your goals. You'll be much more likely to form habits if you can engineer the friction in your environment to help you do so.

Wendy Wood is a research psychologist who devoted the last 30 years to understanding how habits work. She is Provost Professor of Psychology and Business at the University of Southern California, where she also served as Vice Dean of Social Sciences. She is the author of Good Habits, Bad Habits: The Science of Making Positive Changes That Stick.